- Bone Health

- Immunology

- Hematology

- Respiratory

- Dermatology

- Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Neurology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Rare Disease

- Rheumatology

Opinion: A Modified 351(a) Licensing Pathway for Biosimilars

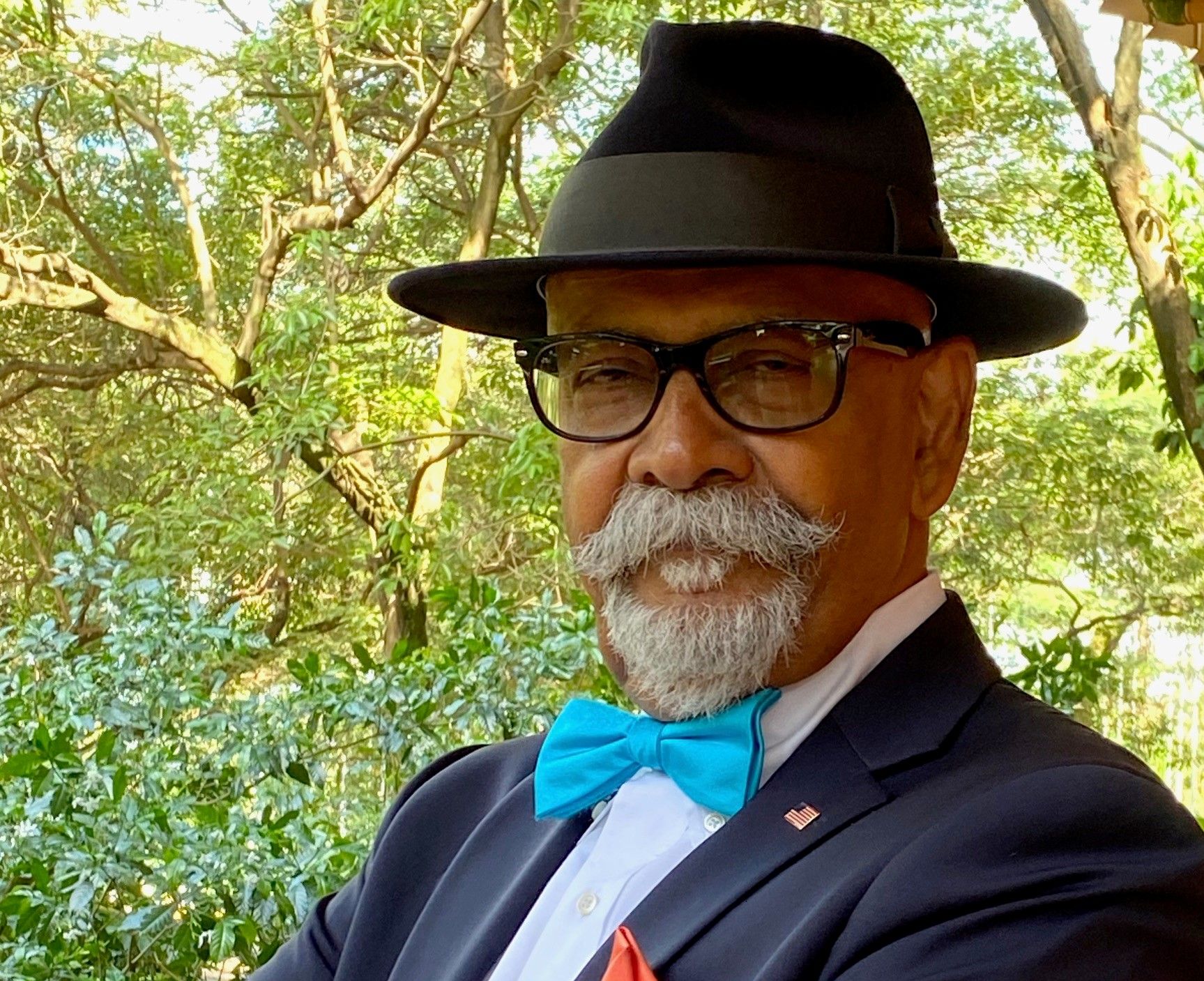

Use of the 351(k) biosimilar approval pathway entails legal challenges, high costs, and potentially higher clinical evidence standards. Sarfaraz K. Niazi, PhD, suggests that using the 351(a) pathway for standalone drugs and copy products may be faster and better. This is part 3 of a series.

This year marks 12 years since the appearance of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA); and, the FDA has approved 30 biosimilar products comprising 10 molecules. A critical analysis of the licensed biosimilars shows a dire need to review the BPCIA pathway to find ways to go around it to expedite the entry of more biosimilars. First, let me share with you a few facts about the licensed biosimilars. Except for 2 biosimilar products, clinical efficacy testing was done for all biosimilar products although they met all other requirements of biosimilarity. None of the products that were tested failed. So, a question arises: What would it be like if these applications were filed under 351(a) for standalone biological products instead of under 351(k)? For example, Teva famously filed for FDA approval of its filgrastim product (Granix) as a standalone biologic. Did it make a difference? No. The biggest problem with BPCIA is the 12-year exclusivity of the reference product. Now that we have reached the 12th anniversary of the BPCIA, let us examine how we can go around the hurdles inherent in the BPCIA.

Using 351(a) for Copies of Approved Drugs

Although the 351(a) pathway is intended for new molecules, it is also available for copies of approved molecules and to add new indications (uses); in a way, it resembles the 505(b)(2), which is a streamlined product approval filing for new chemical generic drugs. The FDA has stated clearly in its guidance for COVID-19 product candidates that, under 351(a), the studies required for product approval may be reduced if a similar product has been approved, essentially inviting the developers to challenge the concessions available for biosimilars. Although there is no reference product required for the development of a copy biologic under 351(a), a dataset that is created comparing the product candidate with a reference product will be accepted as proof of comparable safety and efficacy.

We could unofficially call such imitator products “biosimilars.” There would be no 12-year exclusivity to worry about because originator products would not be involved; there would be no marginal failures in similarity testing and no discussions of minor differences in posttranslational modifications. There would be no patent dance and necessary litigation because the onus of proving intellectual property infringement would lie with the claimant. Manufacturers would have to choose just 1 indication for the purposes of efficacy testing—the same way it is done for biosimilars now. For example, manufacturers could select psoriasis for an adalimumab (Humira) imitation product, and this would be a much cheaper study to conduct. Once approved, prescribers and payers would be able to use the product off-label and compete with Humira for all of its approved indications. I am not recommending breaking any laws; I am presenting facts. For example, bevacizumab (Avastin) is used for age-related macular degeneration as an intravitreal injection, but no bevacizumab products are specifically approved for this use. Does it make a difference if one uses bevacizumab or biologically equivalent products for this purpose? Notwithstanding any special formulation factors, it should be OK.

The cost and time for developing products in this new pathway I am suggesting—a modified 351(a)—would not be higher than for a 351(k) application, but with benefits of getting around the 12-year exclusivity automatically granted to originator products when the filing is made under 351(k)—a big game-changer. Incidentally, when the BPCIA was drafted, I had the privilege of explaining to then–president-elect Barack Obama all about biosimilars. He was opposed to the 12-year exclusivity for originator products, and preferred 8 years at most, although he yielded under opposition from big pharma. This issue becomes more acute if we talk about the creation of biosimilar mRNA vaccines; 12 years is too long a period of exclusivity for the originator products because the vaccine will likely change during that time.

What Constitutes a Biosimilar?

In this column, I am using the term “biosimilar,” and this needs explanation. Biosimilar means a biologically similar product, not a similar product that is biologic. So, we can use the term “biosimilar” to characterize a product approved under 351(a). It need not be essentially associated with BPCIA. However, if you get approval for a standalone product, it will not be eligible for interchangeable status, as was recently awarded to Semglee (insulin glargine). This alternative approval should not be considered as a path opening for interchangeability.

To help my understanding of these issues, I communicated with the FDA about its guidance for COVID-19 products, which reads as follows:

COVID-19 vaccine development may be accelerated based on knowledge gained from similar products manufactured with the same well-characterized platform technology, to the extent legally and scientifically permissible. Similarly, with appropriate justification, some aspects of manufacture and control may be based on the vaccine platform, and in some instances, reduce the need for product-specific data. Therefore, FDA recommends that vaccine manufacturers engage in early communications with [Office of Vaccines Research and Review] to discuss the type and extent of chemistry, manufacturing, and control information needed for development and licensure of their COVID-19 vaccine.

My question to the FDA was, would this advice also apply to other biologics? The answer was, “File a formal meeting request Type B.” This is the FDA asking us to challenge them. I am confident that we can convince the FDA not to require many studies, such as toxicology testing, if we can demonstrate analytical similarity. The pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) studies will be inevitable. We can present the data collected in a comparative study as standalone data to calculate the dose, which we already know, and then demonstrate the PK/PD behavior as additional proof of similarity. A PD response mainly for cytokines where PD parameters are available can be used in lieu of any efficacy testing. Choosing the most straightforward protocol will do; it will not be an equivalence study, nor would it be a noninferiority study, but it can be conducted side-by-side as a monitor arm. The statistical model is relatively simple but requires a bit of creativity. The fact that you would not be able to get interchangeable status is not an issue.

The most significant advantage with the modified pathway I suggest under 351(a) is that you could get into the market at least 5 to 8 years earlier than if you were to enter via the 351(k) pathway; for some products, the 351(k) official biosimilars pathway would be futile if the reference product has changed—a tactic widely adopted by the innovators. You will be able to meet with the FDA in a Type B meeting that is free, and there will be no commitment to paying the yearly BPCIA fee to begin talking to the FDA. The high burden of conducting similarity studies, many of which make no sense, will be reduced. As an example, the biosimilar product may meet all release requirements such as content and potency. However, the product may still fail in comparative testing if the innovator product has lesser variability—which is inconsequential anyway. In short, your biosimilar candidate may be good enough for the patients, but not the FDA.

To recap, I suggest biosimilar developers consider using a modified 351(a) approach for products when establishing biosimilarity is difficult and where there is a need to avoid getting bound by the 12-year exclusivity. The fact that an efficacy and safety study was done for every biosimilar that has been licensed by the FDA (with a couple exceptions) makes the advantages of filing a biologics license application under 351(k) less attractive.

Newsletter

Where clinical, regulatory, and economic perspectives converge—sign up for Center for Biosimilars® emails to get expert insights on emerging treatment paradigms, biosimilar policy, and real-world outcomes that shape patient care.