- Bone Health

- Immunology

- Hematology

- Respiratory

- Dermatology

- Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Neurology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Rare Disease

- Rheumatology

The Underlying Economics of Unbranded Biologics

Unbranded biologics primarily serve to uphold inflated list prices, typically prompted by loss of exclusivity, aiming to safeguard market share and counter biosimilar competition, although forthcoming legislative changes targeting high drug costs could lessen their significance moving forward.

Why do Unbranded Biologics Exist?

FDA defines the term “unbranded biologic” or “unbranded biological product” as an approved brand name biological product that is marketed under its approved biologic license application (BLA) without its brand name (proprietary name) on its label. This is because they are marketed under the same BLA corresponding to the biological brand drug and not different in strength, dosage form, route of administration, or presentation.1 It begs the question that if they are essentially the same drug, then why do 2 variants exist.

The key reason why unbranded biologics exist is to protect the gross-to-net bubble which is becoming increasingly inflated with time. There have been different triggers for manufacturers to launch unbranded variants, but the underlying reason is, almost always, to protect the gross list price of the branded variant.

Inflated List Price

For the brand manufacturer, the list price of the drug defines the gross revenues from the drug. However, net realized revenue is based on the net price, which is substantially lower after all the rebates and discounts provided to different stakeholders like payers, government, health care institutions and channel partners. Rebates to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) constitute a lion’s share of the gross-to-net equation. The gap between the list price and net price has been growing substantially over the years. ‘Drug channels’ estimates that in 2022 the total value of manufacturer’s gross-to-net reductions for Brand-name drugs was about $246 billion.2 Through much of the last decade, list prices have grown year over year (YoY) in the high-single digit percentages, but net prices have been declining YoY for the last 7 years. This widening gap between the gross and net prices is called the gross-to-net bubble.3

High list prices are favorable to PBMs as they negotiate steep rebates from manufacturers, a pre-negotiated portion of these rebates are passed onto the plan sponsors.4 Most PBMs have rebate guarantee clauses in place with the plan sponsors, which forces brand manufacturers to comply with an artificial high-list price high-rebate model. Artificially high list prices cause tremendous burden on patient out-of-pocket spend, as they are calculated as a percentage of list prices. Insulins have been a classic example of this bubble.11

Triggers for Unbranded Biologics

In 2019, the Senate Finance Committee under Charles E. Grassley, held an investigation to examine the factors driving the rising cost of insulin.5 This scrutiny acted as a trigger for Eli Lily and Novo Nordisk to launch unbranded generics (insulins weren’t considered biologic drugs until a rule change went into effect in March 2020) of the brand Humalog (Insulin Lispro) and brand Novolog (Insulin Aspart), at a 50% discount to list price.6, 7 But the brand drugs Humalog and Novolog, continued to be offered at higher list price, as it was a preferred option for majority of the plans and formularies. Even to date, utilization of high list price brand insulins is higher than 90%, as plans prefer them over unbranded low list price variants.12

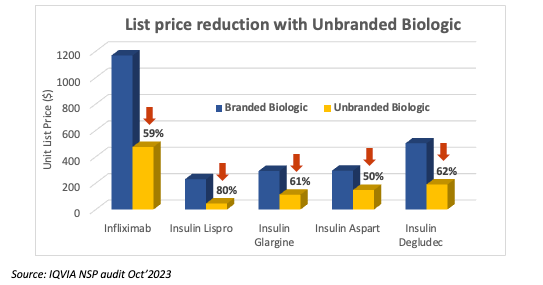

Another key trigger for brands is loss of exclusivity and the entry of biosimilars. Innovative biologic drugs enjoy market exclusivity for long periods of time thanks to the regulatory guidelines and patent protection. Many of these therapies are blockbuster drugs which have multi–billion-dollar revenues. Loss of exclusivity has a significant impact on the organizational fortunes for the innovator. This leads to aggressive market share defense strategies. The launch of unbranded biologics is used as a tactical ploy by brands to retain formulary access to plans which prefer low-list prices. This helps brands to protect market share and slow down biosimilar adoption. Drugs like Remicade (reference infliximab), Lantus (reference insulin glargine), and most recently Humira (reference adalimumab) saw unbranded variants in response to biosimilar entrants.8, 9 All these unbranded variants launched with substantial list price discounts compared to their respective brands.

Source: IQVIA NSP audit Oct’2023

Unbranded Biosimilars

The rebate economics of payers and plan sponsors have forced even biosimilar brands to launch unbranded variants. This seems to be more common in drugs which are heavily covered under pharmacy benefit. Viatris (which recently sold its entire biosimilar portfolio to Biocon) launched an unbranded biosimilar to their brand Semglee (biosimilar insulin glargine), with differential list prices.

Loss of exclusivity for Humira was one of the major market events in 2023. Nine biosimilars launched for Humira and many of them had come up with branded and unbranded variants. This was primarily to offer a twin-wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) strategy. The branded biosimilar with high WAC was offered to plans which preferred rebates, and unbranded biosimilar was offered to plans where lower list prices were preferred. Amgen, Biocon, Sandoz, Bohringer Ingelheim were among the companies which offered 2 variants to Humira biosimilar.10 This trend is expected to continue for biosimilars which would launch for other biologic drugs in the future as well, more so in the self-administered biologics which are covered through pharmacy benefit.

Future of Unbranded Biologics

Multiple legislative changes in the recent past and near future have been aimed at addressing the high cost of prescription drugs. Many of these measures directly or indirectly try to address the gross-to-net bubble. Effective January 1, 2024, the American Rescue Plan Act lifted the cap on the total amount of rebates that Medicaid could collect from manufacturers who raise drug prices substantially over time.13 It created a scenario where, in certain drugs, brand manufacturers will have negative reimbursement for Medicaid prescriptions. Meaning a net loss for every unit of drug sold to a Medicaid patient. This forced insulin manufacturers like Eli Lily, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi to drastically cut the list prices by 70% to 80% for several products late last year. With this change, the list price of branded insulins is now lower than the list price of unbranded insulins. There may not be an incentive to lower the list price of unbranded insulins further below the branded variants, which already stand corrected today. The very objective of unbranded variants now stands defeated. It is uncertain whether unbranded variants would continue to be relevant, at least for insulins where the list price has been corrected.

Another marquee event anticipated is the implementation of inflation reduction act. The proposed benefit redesign shifts significant liability (60%) of drug cost to plan sponsors in the catastrophic phase.14 There may no longer be an incentive for plan sponsors to push patients to catastrophic phase quickly through high list prices for specialty drugs. It is likely to have an impact on the use of high-list price, high-rebate strategies by plan sponsors. If the preference shifts to reasonable list prices, then the need for unbranded biologics may be further dampened.

However, brands may continue to use unbranded biologics as a strategy for market share defense when biosimilar players enter, much like how authorized generics have been at play for many years in the small molecule drugs.

Author Bio

Dinakaran is an accomplished commercial professional with rich experience of over 12 years in the pharmaceutical industry. He has an extensive understanding of the US commercial landscape and its key economic drivers, specifically in generic injectables and biosimilars. He is currently serving as the Head of Commercial Strategy & Insights for Biologics in North America for Dr Reddys Laboratories. His role extends to providing valuable insights into pricing considerations, competitive intelligence, and market dynamics, crucial for driving product adoption and profitability objectives. During his long tenure, he has handled multiple roles across Sales, strategy, pricing, and product management.

References

- Purple Book database of licensed biological products. FDA. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.ahip.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/MADemo_Report2015.pdf

- Four trends that will pop the $250 billion gross-to-net bubble—and transform PBMs, market access, and benefit design. FDA. April 4, 2023. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.drugchannels.net/2023/04/four-trends-that-will-pop-250-billion.html

- Prescription drug rebates, explained. KFF. July 26, 2019. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://www.kff.org/medicare/video/prescription-drug-rebates-explained/

- Campbell M. What employers need to know about drug rebates. RxBenefits. June 21, 2022. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://www.rxbenefits.com/blogs/understanding-the-role-of-drug-rebates/

- United States Senate Finance Committee. Insulin: Examining the Factors Driving the Rising Cost of a Century Old Drug. 2021. GAO-12-565R. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Grassley-Wyden%20Insulin%20Report%20(FINAL%201).pdf

- Liu A. Lilly answers insulin price-hike critics with 50% off Humalog generic. Fierce Pharma. March 4, 2019. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/lilly-offers-generic-humalog-at-half-price-amid-bipartisan-pressure-rising-insulin-costs

- Schaffer R.Novo Nordisk announces half-price, authorized generic insulins. Fierce Pharma. September 9, 2019. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://www.healio.com/news/endocrinology/20190909/novo-nordisk-announces-halfprice-authorized-generic-insulins

- Janssen’s unbranded infliximab is Remicade® without the brand name. Janssen. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.infliximab.com/patient/learn-about-infliximab/

- Insulin glargine U-100 – the unbranded biologic that is identical to Lantus. Sanofi. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.lantus.com/how-to-use/insulin-glargine-u100

- Kansteiner F.Boehringer Ingelheim embraces dual-pricing tactic with launch of unbranded Humira biosimilar. Fierce Pharma. October 4, 2023. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/boehringer-ingelheim-jumps-industrys-dual-pricing-trick-unbranded-humira-biosimilar

- Dickson SR, Gabriel N, Gellad WF, Hernandez I. Assessment of commercial and mandatory discounts in the gross-to-net bubble for the top insulin products from 2012 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. Published online June 14, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.18145

- George K, Woollett G. Insulins as drugs or biologics in the USA: What difference does it make and why does it matter? BioDrugs. 2019; 33(5):447-451. doi:10.1007/s40259-019-00374-1

- Williams E. What are the implications of the recent elimination of the Medicaid prescription drug rebate cap? KFF. January 16, 2024. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/what-are-the-implications-of-the-recent-elimination-of-the-medicaid-prescription-drug-rebate-cap/

- Cubanski J, Neuman T, Freed M. Explaining the Prescription Drug Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. KFF. January, 24, 2023. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/#:~:text=The%20Inflation%20Reduction%20Act%20makes,D%20Low%2DIncome%20Subsidy%20Program

Newsletter

Where clinical, regulatory, and economic perspectives converge—sign up for Center for Biosimilars® emails to get expert insights on emerging treatment paradigms, biosimilar policy, and real-world outcomes that shape patient care.