- Bone Health

- Immunology

- Hematology

- Respiratory

- Dermatology

- Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Neurology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Rare Disease

- Rheumatology

Utilizing Oncology Biosimilars to Minimize the Economic Burden Associated With Cancer Treatment: Managed Care Considerations

Statement of Need

The high cost of therapies for treatment of cancer places a substantial burden on the United States healthcare system. In recent years, there has been increased attention to the cost-savings benefits associated with clinical uptake of biosimilars and their market availability, with several biosimilars with oncology-related indications currently available. Though the biosimilar development process has contributed to price reductions and increased patient access to care, misconceptions about biosimilar safety and efficacy as well as inconsistent prescribing patterns have emerged as main barriers to their use in clinical practice. However, this hesitation from a clinical standpoint is not necessarily matched by payers or formulary decision makers in the oncology space. Earlier detection of cancer and longer duration of therapy has spurred discussion about initiation of biosimilars for newly diagnosed patients requiring treatment, but incorporation of biosimilars into formularies and institution protocols remain a challenge. There is clear urgency within the healthcare system to initiate the inclusion of biosimilars into treatment pathways for cancer, and pharmacists who care for patients with cancer have an important role in providing consistent messaging to both healthcare professionals and patients about biosimilars.

Introduction

Biological products, which are also referred to as biologic agents or biologics, are generally large and complex molecules produced from living entities such as microorganisms, plant, or animal cells.1 Biologics are used in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of many conditions, including those for cancer.1 Over the past few decades, advancement in biomedical technology has led to increased commercialization of biologics, which has impacted cancer care. As cancer care is associated with high cost, the production of a “biosimilar” product that is comparable in clinical efficacy has generated interest to mitigate healthcare-associated costs and improve access to care.2

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA), enacted in 2010 in association with the Affordable Care Act (ACA), created a regulatory pathway for Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of biosimilars.3 This has allowed an increase in biosimilars available in the United States (US) market, and has also improved access to care, particularly within the oncology setting.3 However, there is still variability in prescriber acceptance and use of biosimilars, due to potential misconceptions with clinical efficacy, as well as challenges with formulary management.4 From the payer perspective, biosimilar products show promise in reducing healthcare costs.5 Managed care professionals are well positioned to increase uptake of oncology biosimilars in patient care.

Biologic Background and Approval Process

When discussing biologics, the original product is known as the “reference product,” which is FDA approved based on a full review of safety and efficacy data. The reference product is used to produce a “biosimilar,” which is a biological product that undergoes an extensive review process to determine that it is “highly similar” to the reference product.1 Ultimately, the manufacturer of the biosimilar needs to show, through analysis of the structure and function of both the reference product and the biosimilar, that the 2 products have no meaningful differences in terms of purity, chemical identity, and bioactivity.1,6 Minor differences between the 2 products are acceptable, given the nature of the manufacturing process for biologics; however, biosimilar products must be carefully monitored from lot to lot to control for potential variations and ensure consistency.1,6 This is unlike generic drugs, where the manufacturer of a generic must only demonstrate bioequivalence compared with the brand product. Additionally, the manufacturer of a biosimilar needs to demonstrate that there are no clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar and reference product, often through additional clinical trials.1,6

The approval process for a biosimilar product is unique. The BPCIA created an abbreviated licensure pathway, commonly known as 351(k).3,7 The BPCIA also defined the concept of “interchangeability” between products, meaning the biological product may be substituted for the reference product without the intervention of the prescriber. To receive interchangeability status, the manufacturer of a biosimilar must demonstrate the product produces the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient. Additionally, for a product that is administered more than once to an individual, the clinical impact (eg, safety and efficacy) from changing between use of the biosimilar and the reference product cannot be greater than the risk of continuing to use the reference product. Currently, none of the FDA-approved biosimilars with oncology indications are considered interchangeable. Depending on state laws, a prescription for a reference product may be changed to a biosimilar product with physician approval. This is a key difference between a biosimilar and a generic, as generic products may be automatically substituted for brand, unless otherwise specified.1 Additionally, biosimilar products may not be approved for all of the same indications as the reference product.8

Economic Benefit of Oncology Biosimilars

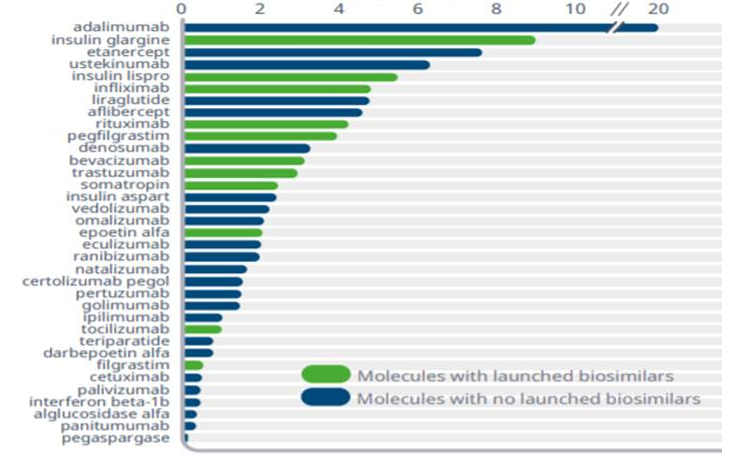

Cost of cancer care is rapidly challenging national budgets for healthcare, impacting overall healthcare financing.2 Oncology spend continues to rise; as the incidence of some malignancies increases, cancer therapies may be initiated earlier due to improvements in early cancer detection, and therapy may be longer due to prolonged patient survival.9 From 2018 to 2019, health plans saw an increase of 15% to 22% in oncology spend.10 Currently, the oncology pipeline has more than 700 drugs in clinical trials, and it is anticipated that there will be a 105% growth for the oncology category by 2024 (Figure 13).10 The cost of some chemotherapies and targeted therapies has continued to escalate dramatically. For example, from 2005 to 2017, the cumulative cost increase was 29% for bevacizumab, 78% for trastuzumab, and 85% for rituximab (Figure 23).11 The availability of biosimilars for these biologics is an important opportunity to lower healthcare costs and expand access to more oncology patients. A recent RAND Corporation analysis estimated that biosimilars could save the US healthcare system $54 billion over the next decade, with potential savings ranging from $25 billion to $150 billion.5

Figure 1: Biosimilars Based on Approval Status3

Figure 2: 2019 Spend of Approved and Pipeline Biosimilars, US $Bn3

While costs of care are rising, the ability of patients to pay for care is impacted; the cost of oncology biologics may exceed $10,000 per month, which is double the US median monthly household income.12 Compared with traditional chemotherapy agents, biological products are more costly to produce due to complex physiochemical structures, which has impacted the cost of cancer care.13 Payers may consider incentivizing for the use of therapy regimens that are lower in cost and provide the same level of compendia recommendation. As biosimilars have shown no clinical meaningful difference from the reference product, there is the potential for biosimilars to help control healthcare costs and also maintain quality cancer care.

Until the BPCIA was enacted in 2010, patent litigation prevented most biosimilars from reaching the market. In 2018, biosimilars accounted for less than 2% of the total US biologics market.9 In 2019, there was a dramatic increase in both FDA approvals and utilization of biosimilars. The 3 biosimilars launched in 2019 achieved significant uptake within their first year, with bevacizumab leading at 42%, trastuzumab at 38%, and rituximab at 20%, with use continuing to increase.3 In comparison, when filgrastim, the first biosimilar, was approved, there was only a market share of 25% in the first year. This increased to 80% in 2019, further illustrating improved access to biosimilars.3

The potential cost impact of the biosimilars is often compared with European practices, as the European Medicines Agency has now approved the highest number of biosimilars worldwide after introduction of their biosimilar guidelines in the early 2000s.14 The use of biosimilars has allowed for increased access to care and treatment, allowing for potential improvements in clinical outcomes.14 As more biosimilars become available after receiving regulatory approval, adoption in clinical practice is expected to increase.

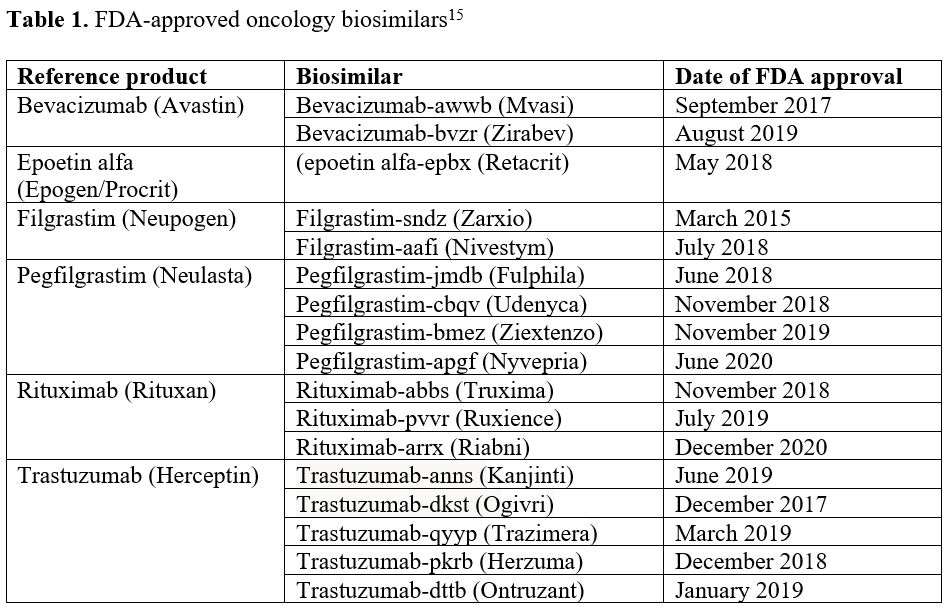

In the oncology space, there are now 17 biosimilars available for chemotherapeutic agents and supportive care medications, including filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, epoetin alfa, rituximab, trastuzumab, and bevacizumab (Table 115). The pattern of biosimilar use in clinical practice is not consistent and influenced by payer formulary management differences.3

Payer Considerations

For payers in the United States, the advent of biosimilars has the potential to counter rising costs in oncology care. However, the road to successful incorporation of biosimilars into clinical practice has been challenging due to formulary considerations, the need for efficacy data, concerns with substitution between products, and an overall lack of prescriber awareness.16 Specifically, there are concerns due to the potential for immunogenicity, or potential immune response due to slight molecular alteration.17 Whether the immune response would be clinically important is difficult to predict, with potential manifestations including changes in pharmacokinetic activity, altered efficacy, infusion-related reactions, or cross-reactivity to the therapeutic protein. Without the designation for interchangeability, provider concerns include changing between reference product and biosimilar product numerous times due to theoretical risk of immunogenicity. Furthermore, a loss or change in efficacy is also a concern. Data from Europe assessing hundreds of millions of treatments have shown no significant increase in clinically relevant safety signals. The FDA has placed a strong emphasis on reviewing immunogenicity risk and will not allow biosimilars to be approved if there are unanswered questions when reviewing immunogenicity data. Nonetheless, providers in the United States continue to be cautiously optimistic to approach using the biosimilar initially.4

On the other side, payers have been much more aggressive with biosimilar adoption. Payer decisions on biosimilar use are based on a variety of factors, including product evidence, characteristics of the product, manufacturer and supplier reliability, dosage forms, patient adherence, cost, as well as an evaluation of contracts and rebates.16 The most common type of payer management is through prior authorization and step therapy.18 In all categories with a preferred biosimilar, patients will likely be required to “step through,” meaning therapies must be prescribed in a certain order to ensure insurance coverage. For example, the preferred biosimilar(s) must be administered before receiving nonpreferred biosimilar(s) or the originator product.19 In the oncology space, it is far more accepted to introduce biosimilars into the treatment of patients who are new to treatment, and it may be more difficult to use the agents for those who are mid-treatment or are stable in their current treatment protocol.

One additional complexity is the specific naming rules for biosimilars, which reduces the risk of inadvertent substitution.1 This also implies that payers must stipulate the specific biosimilar by its distinguishable, nonproprietary name, include the four-letter suffix following the core name of the drug, attached by a hyphen.1 Additionally, as biosimilars are not interchangeable with the originator biologic agent, payers continue to make product-by-product decisions before adding a biosimilar to system formularies. The decision for formulary addition is made following a complete clinical and financial review of each biosimilar product, as well as the reference product, to determine overall value.16 Additional elements that contribute to the value of a biosimilar in the decision-making process include product quality established through extensive analytical and functional assessments during product development; provider-focused education; provider engagement; manufacturer reliability of quality and the supply chain; and additional services such as, for example, anticounterfeit protection.20

Another major obstacle for the adaption of biosimilars is the potential misconception by patients and prescribers that biosimilars are associated with decreased efficacy because they are less expensive. Long-term follow-up of data from the integration of biosimilars into practice in Europe and the strict standards set by the FDA will help improve perceptions over time, but education is needed to mitigate concerns regarding efficacy and safety.21 A survey conducted in 2016 among prescribers identified knowledge as a major barrier in the incorporation of biosimilars into clinical practice, specifically in provider understanding of “totality of evidence” used when evaluating the biosimilar to the reference product.4 This provides a key opportunity for pharmacist involvement in providing physician and patient education to aid the understating of and successful uptake of biosimilars in the United States.

Despite many challenges, payers are hopeful that biosimilars will spur price reductions through competition, both with the reference agent and with other biosimilars. Originally, projections in 2015 showed expected reductions for biologic spend to be approximately 4%, or $44.2 billion, with newer projections being close to 8%.22,23 Reductions may become larger over time as processes improve for developing and improving biosimilars. In 2019, reductions in average selling price (ASP) for biosimilars and originator products averaged between 15% and 45%, with filgrastim showing the greatest price reduction. Bevacizumab, rituximab, and trastuzumab showed an ASP price reduction of $500 to $1900 for a standard course of treatment.3 As experience with biosimilar products increases, regulatory restrictions may ease, which will allow for lower development and licensing costs. Direct cost reductions are anticipated to offset the incremental costs of developing and introducing innovator drugs to the healthcare field.22,23

Ultimately, overall costs and cost-savings will be key for acceptance of biosimilars in clinical practice and in the market. Negotiations between payers and manufacturers will likely continue as competition for formulary approval increases. Government and accountable care organizations may be involved in pricing and formulary negotiations, where a discount may be given for formulary placement. Pharmacy benefits managers and third-party payers may impose pressures on manufacturers to reduce costs further through rebates and discounts. Savings over the next 5 years as a result of biosimilar competition are projected to exceed $100 billion.3

Billing and Reimbursement

Each biosimilar receives its own unique healthcare common procedure coding system (HCPCS) reimbursement code. This impacts product management in terms of billing and reimbursement, as well as utilization tracking for each biosimilar through its designated HCPCS code.16

Depending on the biosimilar, most billing for a drug is divided between physician buy-and-bill and hospital outpatient reimbursement. A very small portion goes through specialty pharmacy distribution or home infusion. According to the National Board of Prior Authorization Specialists, “buy-and-bill” is a process for physician offices to acquire medications that providers can administer in the office.24 Providers are responsible for ordering and purchasing the drug, then billing payers for reimbursement. Physician payment typically includes a “margin,” which is a percentage surplus based on the ASP of the product administered. The more expensive the product, the higher the margin. Uptake of biosimilars is strongly influenced by the reimbursement policies of these biosimilars. The ACA requires Medicare Part B reimbursement value for a biosimilar to be based on the sum of the drug’s ASP plus a fixed percentage of the reference product’s price.25 As a result, reimbursements by Medicare for biosimilars are now equivalent to payments for reference products.

Value-based Care

Value-based care allows for providers, including hospitals and physicians, to be paid based on patient outcomes, with an ultimate goal of improving quality of patient care, while also controlling costs.20 For example, physicians may be rewarded for providing quality care that is also cost-efficient.20,26 This model is an alternative to traditional fee-for-service reimbursement, which pays providers retrospectively for services delivered based on bill charges or annual fee schedules. The value-based reimbursement model is designed to shift some of the treatment risks to providers by increasing provider responsibility on the overall care of the patient, and in return, rewarding the provider for excellence of care. Given the lower costs of biosimilars and similar clinical qualities, they are likely to play a significant role in value-based care systems. “Value” is a more nebulous term than cost and encompasses many fewer tangible attributes such as brand acceptance, trust, reliability, and consistency of performance and supply.20 In a value-based care model, the metrics of value would be predefined to encompass different aspects of the clinical work. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has programs with such incentive payments for quality care, and it is expected that payments from CMS will be linked to outcomes specifically in the oncology setting. Biosimilars are of particular interest in this payment model as they have the potential to mitigate cost while still allowing for quality care through expansion of services.20 Clinical data have shown that there is improved access to care with biologics, as well as a reduction in cost. In Europe, use of biosimilar supportive care drugs filgrastim and epoetin alfa allowed for increased access to care based on cost.27,28 Similar findings have been seen in the United States.22

One example of value-based care when it comes to biosimilars is the development of accountable care organizations (ACOs), where groups of doctors, hospitals, and other healthcare providers that provide coordinated care to Medicare patients are reimbursed based on meeting certain quality metrics. The ACOs assume shared risk as to the cost of healthcare, and therefore are much more motivated to choose therapies of similar clinical portfolio but lower cost. The ACOs hold considerable influences over physician decisions to use biosimilars and as such, driving significant uptake of oncology biosimilars in 2019.16 On another note, the economic benefit of the biosimilars toward cost-savings may also be passed directly on to patients in the form of reduced out-of-pocket costs. Many patients are responsible for a portion of shared healthcare cost in the form of a co-pay or a co-insurance. The actual co-pay structure may vary depending on benefit design. Typical co-insurance is 18%.29 Patients receiving a biosimilar paid on average 12% to 45% less out of pocket than those receiving the reference product.30 These cost data may impact decisions of managed care organizations to incorporate biosimilars into system formularies.

In summary, there are many considerations for payers to evaluate when making a formulary decision for a biosimilar product. These include the totality-of-evidence approach for demonstrating biosimilarity (eg, analytical/functional similarity, efficacy, and safety); economic benefits, manufacturing considerations, product distribution/access, physician preferences, and patient preferences. Also, payers must consider the impact of state laws regarding interchangeability between products. In the United States, further real-world experience with biosimilars is needed to more fully appreciate biosimilar value and potential, as well as increased patient access to cancer care with biologics. Additionally, pharmacists can assist in education of patients and providers regarding biosimilars and their clinical value in healthcare.

References

1. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Biosimilar and interchangeable products. October 23, 2017. Accessed June 19, 2021. www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-and-interchangeable-products#biological

2. Sullivan R, Peppercorn J, Sikora K, et al. Delivering affordable cancer care in high-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(10):933-980. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70141-3

3. IQVIA Institute Report. Biosimilars in the United States 2020-2024: competition, savings, and sustainability. September 29, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/biosimilars-in-the-united-states-2020-2024

4. Cohen H, Beydoun D, Chien D, et al. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physicians. Adv Ther. 2017;33(12):2160-2172. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0431-5

5. Mulcahy AW, Hlavka JP, Case SR. Biosimilar cost savings in the United States: initial experience and future potential. RAND Health Q. 2018;7(4):3.

6. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Biosimilars. Updated July 28, 2021. Accessed August 3, 2021. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/

7. Franklin J. Biosimilar and Interchangeable Products: The U.S. FDA Perspective. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 2018. Accessed June 19, 2021. www.fda.gov/media/112818/download

8. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Prescribing biosimilar products. Accessed July 30, 2021. www.fda.gov/media/108103/download

9. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. Medicine use and spending in the U.S.: a review of 2018 and outlook to 2023. May 9, 2019. Accessed June 21, 2021. www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-use-and-spending-in-the-us-a-review-of-2018-and-outlook-to-2023

10. Magellan Rx Management Medical Pharmacy Trend Report, 2020, eleventh edition. 2021. Accessed June 9, 2021. https://www1.magellanrx.com/documents/2021/05/2020-mrx-medical-pharmacy-trend-report.pdf

11. Gordon N, Stemmer SM, Greenberg D, Goldstein DA. Trajectories of injectable cancer drug costs after launch in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):319-325. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.2124

12. Kantarjian H, Patel Y. High cancer drug prices 4 years later—progress and prospects. Cancer. 2017;123(8):1292-1297. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30545

13. Thill M, Thatcher N, Hanes V, Lyman GH. Biosimilars: what the oncologist should know. Future Oncol. 2019;15(10):1147-1165. doi: 10.2217/fon-2018-0728

14. European Medicines Agency. Biosimilars in the EU: information guide for healthcare professionals. 2019. Accessed June 21, 2021. www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Leaflet/2017/05/WC500226648.pdf

15. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA-approved biosimilar products. Updated July 29, 2021. Accessed July 30, 2021. www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-product-information

16. Smeeding J, Malone DC, Ramchandani M, Stolshek B, Green L, Schneider P. Biosimilars: considerations for payers. P T. 2019;44(2):54-63.

17. Griffith N, McBride A, Stevenson JG, Green L. Formulary selection criteria for biosimilars: considerations for US health-system pharmacists. Hosp Pharm. 2014;49(9):813-825. doi: 10.1310/hpj4909-813

18. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Advantage Prior Authorization and Step Therapy for Part B Drugs. Updated August 7, 2018. Accessed July 9, 2021. www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-advantage-prior-authorization-and-step-therapy-part-b-drugs

19. Avalere Health. Use of Step Through Policies for Competitive Biologics Among Commercial US Insurers. May 7, 2018. Accessed July 9, 2021. https://avalere.com/insights/use-of-step-through-policies-for-competitive-biologics-among-commercial-us-insurers

20. Patel KB, Arantes LH Jr, Tang WY, Fung S. The role of biosimilars in value-based oncology care. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:4591-4602. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S164201

21. Lyman GH, Balaban E, Diaz M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: biosimilars in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(12):1260-1265. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.4893

22. Mulcahy AW, Predmore Z, Mattke S. The cost savings potential of biosimilar drugs in the United States. RAND Corporation. 2014. Accessed June 25, 2021. www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE127.html

23. Milliman White Paper. Understanding biosimilars and projecting the cost savings to employers:update. Milliman. June 29, 2015. Accessed August 3, 2021. www.milliman.com/-/media/milliman/importedfiles/uploadedfiles/insight/2015/understanding-biosimilars.ashx

24. DeMarzo A. What is buy and bill? National Board of Prior Authorization Specialists. March 22, 2021. Accessed June 21, 2021. www.priorauthtraining.org/what-is-buy-and-bill/

25. Singh SC, Bagnato KM. The economic implications of biosimilars. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(16 suppl):s331-340.

26. NEJM Catalyst. What is value-based healthcare? January 1, 2017. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0558

27. Aapro M, Cornes P, Abraham I. Comparative cost-efficiency across the European G5 countries of various regimens of filgrastim, biosimilar filgrastim, and pegfilgrastim to reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2012;18(2):171-179. doi: 10.1177/1078155211407367

28. Aapro M, Cornes P, Sun D, Abraham I. Comparative cost efficiency across the European G5 countries of originators and a biosimilar erythropoiesis-stimulating agent to manage chemotherapy-induced anemia in patients with cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2012;4(3):95-105. doi: 10.1177/1758834012444499

29. 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey. Kaiser Family Foundation. October 3, 2018. Accessed June 9, 2021. www.kff.org/report-section/2018-employer-health-benefits-survey-summary-of-findings/

30. Socal M, Ballreich J, Chyr L, Anderson G. Biosimilar Medications − Savings Opportunities for Large Employers. A report for ERIC – the ERISA Industry Committee. Department of Health Policy and Management. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. March 2020. Accessed June 9, 2021. www.eric.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/JHU-Savings-Opportunities-for-Large-Employers.pdf

Newsletter

Where clinical, regulatory, and economic perspectives converge—sign up for Center for Biosimilars® emails to get expert insights on emerging treatment paradigms, biosimilar policy, and real-world outcomes that shape patient care.